A newly discovered, “potentially hazardous” asteroid almost the size of the world’s tallest skyscraper is set to tumble past Earth just in time for Halloween, according to NASA.

The asteroid, called 2022 RM4, has an estimated diameter of between 1,083 and 2,428 feet (330 and 740 meters) — just under the height of Dubai’s 2,716-foot-tall (828 m) Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world. It will zoom past our planet at around 52,500 mph (84,500 km/h), or roughly 68 times the speed of sound, according to NASA (opens in new tab).

At its closest approach on Nov. 1, the asteroid will come within about 1.43 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) of Earth, around six times the average distance between Earth and the moon. By cosmic standards, this is a very slender margin.

Related: Why are asteroids and comets such weird shapes? (opens in new tab)

NASA flags any space object that comes within 120 million miles (193 million km) of Earth as a “near-Earth object” and classifies any large body within 4.65 million miles (7.5 million km) of our planet as “potentially hazardous.” Once flagged, these potential threats are closely watched by astronomers, who study them with radar for signs of any deviation from their predicted trajectories that could put them on a devastating collision course with Earth.

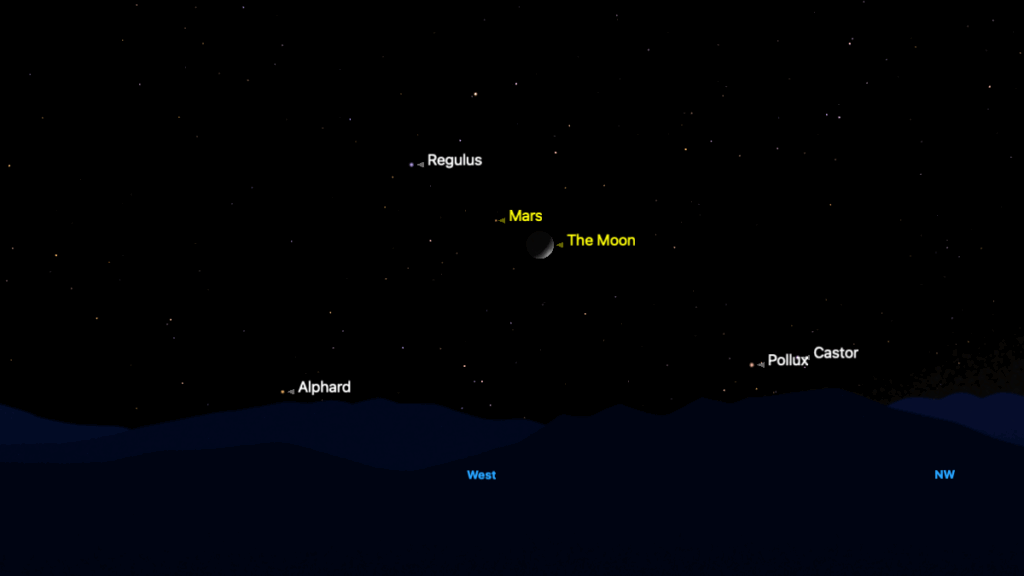

No danger, but newly-discovered asteroid 2022 RM4 will pass less than 6 lunar distances on November 1. Possibly as wide as 740 meters, it will brighten to mag 14.3, well within reach of backyard telescopes. @unistellar This is very close for an asteroid this size. #2022RM4 pic.twitter.com/Z8khblg3GqOctober 5, 2022

NASA tracks the locations and orbits of roughly 28,000 asteroids, pinpointing them with the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) — an array of four telescopes able to perform a total scan of the entire night sky every 24 hours.

Since ATLAS was brought online in 2017, it has spotted more than 700 near-Earth asteroids and 66 comets. Two of the asteroids detected by ATLAS, 2019 MO and 2018 LA, actually hit Earth, the former exploding off the southern coast of Puerto Rico and the latter crash-landing near the border of Botswana and South Africa. Fortunately, those asteroids were small and didn’t cause any damage.

NASA has estimated the trajectories of all the near-Earth objects beyond the end of the century. The good news is that Earth faces no known danger from an apocalyptic asteroid collision for at least the next 100 years, according to NASA (opens in new tab).

Related: 8 ways to stop an asteroid: Nuclear weapons, paint and Bruce Willis

RELATED STORIES

But this doesn’t mean that astronomers think they should stop looking. Though the majority of near-Earth objects may not be civilization-ending, such as the planet-busting comet in the 2021 satirical disaster movie “Don’t Look Up,” there are plenty of devastating asteroid impacts in recent history to justify the continued vigilance.

For instance, in March 2021, a bowling ball-size meteor exploded over Vermont (opens in new tab) with the force of 440 pounds (200 kilograms) of TNT. In 2013, a meteor that exploded in the atmosphere above the central Russian city of Chelyabinsk generated a blast roughly equal to around 400 to 500 kilotons of TNT, or 26 to 33 times the energy released by the Hiroshima bomb (opens in new tab). During the 2013 explosion, fireballs rained down over the city and its environs, damaging buildings, smashing windows and injuring approximately 1,500 people.

If astronomers were to ever spy a dangerous asteroid headed our way, space agencies around the world are already working on possible ways to deflect it. On Sept. 26, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft redirected the non-hazardous asteroid Dimorphos by ramming it off course (opens in new tab), altering the asteroid’s orbit by 32 minutes in the first test of Earth’s planetary defense system.

China has also suggested (opens in new tab) it is in the early planning stages of an asteroid-redirect mission. By slamming 23 Long March 5 rockets into the asteroid Bennu, which is set to swing within 4.6 million miles (7.4 million km) of Earth’s orbit between the years 2175 and 2199, the country hopes to divert the space rock from a potentially catastrophic impact with our planet.

Originally published on Live Science.